Saramago: Prophet of our Times

Saramago: Prophet of our Times

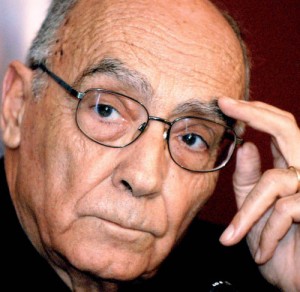

Portuguese writer José Saramago is considered today one of the most outstanding writers in the world. Not only for his commitment to his art but also because of his espousal of social causes and of the amelioration of the condition of the human being in this world.

Awarded the Nobel prize for Literature – the first writer in Portuguese to do so — Saramago has been undeterred by fame or fortune and remains the person he always was. He says -‘I am the same person I was before receiving the Nobel Prize. I work with the same regularity, I have not modified my habits, I have the same friends.’

This nonchalance was however not shared by his Portuguese editor Zeferino Coelho. When the Nobel announcement came in October 1998 Saramago was just about to board a plane out of Germany after the Frankfurt Book Fair. With his characteristic wryness he said, ‘I was not born for all this glory.’ Zeferino however replied brightly ‘You may not have been made for this glory, but I was!’ Since then Saramago’s work has been translated widely from the Portuguese into English and several other languages giving him a globalized following.

Born in 1922 in the village of Azinhaga in the province of Ribatejo about 60 miles north-east of Lisbon, Saramago had to abandon his high-school studies to earn a living as a mechanic. But he never forgot his land, his roots, nor, sometimes on hot summer nights, after supper, sleeping under the fig tree with his grandfather. ‘With sleep delayed, night was peopled with the stories . . . my grandfather told: legends, apparitions, terrors, unique episodes, old deaths, scuffles with sticks and stones, the words of our forefathers, an untiring rumour of memories that would keep me awake while at the same time gently lulling me.’

In his Nobel lecture he says, ‘If my grandfather had been a rich landowner and not an illiterate pig breeder, I wouldn’t be the man I am today. If I could choose my own background – even with the cold of the winters, the heat of the summers, sometimes going hungry – I wouldn’t change a thing.’

It is difficult to define Saramago’s work – because he is so polyvalent, ‘playful’ and creative. He has published plays, short stories, novels, poems, libretti, diaries, and travelogues. Almost always, the backdrop is Portugal.

Saramago’s first book was a collection of poems Os Poemas Possiveis / Possible Poems (1966) when he was 44. His first novel was published 11 years later. In this novel, Manual de Pintura e Caligrafia /Manual of Painting and Calligraphy (1977) he spans the canvas of a painter as well as a writer, unfolding the genesis of art.

Italian composer Azio Corghi based his opera Blimunda on Saramago’s novel Memorial do Convento / Baltasar and Blimunda (1982). With sounds from Domenico Scarlatti’s harpsichord, the story is about ‘three Portuguese fools from the 18th century in a time and country where superstition and the fires of the Inquisition flourished.’

In O Ano da Morte de Ricardo Reis / The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis (1984) he resurrects the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935) and uses the aliases of Pessoa to comment on historical events of the time, viz. Franco’s crushing of Spain’s Republican government, Mussolini’s conquest of Abyssinia, Hitler’s invasion of Czechoslovakia —all this while under the dictatorship of Antonio Salazar in Portugal, a regime which lasted 48 years since 1926.

Portugal’s exclusion from Europe is the subject of Saramago’s next novel A Jaganda de Pedra / A Stone Raft (1986). A series of supernatural events results in the Iberian peninsula (Spain and Portugal) breaking free so that it starts to float into the Atlantic initially heading for the Azores. Saramago is not bound by traditional conventions of the novel as one can see, ‘The novel is not so much a literary genre,’ he says, ‘but a literary space, like a sea filled by many rivers.’

Saramago’s writing is sometimes referred to as magic realism. This is because he has combined in his work, myths, the history of Portugal and a surrealistic imagination. Consider his delightfully bizarre opening of Viagem a Portugal / Journey to Portugal (1990). Almost in the mock-heroic vein of Cervantes Don Quixote, Saramago stands exactly on the Spanish-Portuguese border over the river Douro, to address the fish beneath, and – he, being atheist – asks for their blessings for his travels:

‘This was the first traveler ever to pull up in his car, with the engine already in Portugal but the petrol tank still in Spain . . . Then across the deep dark waters . . . the traveler’s voice could be heard preaching to the fish in the river:

“Gather round, fishes, those of you to the right still in the River Douro and those of you to the left in the River Duero, come closer all of you and advise me what language you speak when you cross the watery frontiers beneath, and whether down there you also produce passports and visas as you enter and depart”’

The subtitle of the novel Journey to Portugal is ‘A Pursuit of Portugal’s History and Culture.’ It was nevertheless a curious turn of fate that forced Saramago to leave Portugal in protest in 1992 and settle in the Canary Islands of Spain. This when the Portuguese government, apparently under pressure from the Catholic Church, scuttled attempts to nominate his controversial novel The Gospel According to Jesus Christ (1991) for a European literary prize. Some feel his exile has made him less relevant, but to others he is now the voice of a more universal conscience.

He does have a foothold in Portugal, so to speak — an apartment lined with the books he has written — in Lisbon, which he visits occasionally with his Spanish wife, and official Spanish translator, Pilar del Rio. 30 years younger than Saramago they married in 1988. Ilda Reis was his first wife. Their only child, Violante, was born in 1947.

Saramago has always been in the forefront of political struggles, be it Spain, Portugal or Latin America. ‘I can’t imagine myself outside any kind of social or political involvement’ – he said. A member of Portugal’s communist Party since 1969, he has been an impassioned espouser of the Palestinian cause and sees eye to eye with the views of Venezulean President Hugo Chavez.

In a speech in Paris entitled ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’ (2002) he castigated the ‘bureaucratised trade unionism’ which he said ‘is largely responsible for the social torpor that has accompanied economic globalisation.’ ‘Unless we intervene in time,’ he continued, ‘and that time is now – the cat of economic globalisation will inevitably devour the mouse of human rights.’ Saramago believes, ‘As citizens, we all have an obligation to intervene and become involved – it’s the citizen who changes things.’ Even some of his poetry espouses this cause, inspite of a streak of the surreal:

Poema À Boca Fechada

Não direi:

Que o silêncio me sufoca- e amordaça.

Calado estou, calado ficarei,

Pois que a língua que falo é de outra raça.

Palavras consumidas se acumulam,

Se represam, cisterna de águas mortas,

Ácidas mágoas em limos transformadas,

Vaza de fundo em que há raízes tortas.

Não direi:

Que nem sequer o esforço de as dizer merecem,

Palavras que não digam quanto sei

Neste retiro em que me não conhecem.

Nem só lodos se arrastam, nem só lamas,

Nem só animais bóiam, mortos, medos,

Túrgidos frutos em cachos se entrelaçam

No negro poço de onde sobem dedos.

Só direi,

Crispadamente recolhido e mudo,

Que quem se cala quando me calei

Não poderá morrer sem dizer tudo.

Poem to the Shut Mouth

I shall not say:

That the silence suffocates me — and gags.

Silent I am, silent I shall be

Because the language I speak is of another kind.

Words consumed, accumulate,

They stagnate, a cistern of dead waters,

Acid anguish turns to lime

Leaks below where crooked roots lie.

I shall not say:

That it deserves the effort to name them,

Words that do not say how much I know

In this retreat where no one knows me.

Not only mud is dragged, also sludge

Not only animals float, dead, fears

Turgid fruits in branches entwine themselves

In the dark well where fingers climb.

I shall only say

Crisply, secluded and mute

that whoever keeps silent when I was silent

Cannotdie without saying everything.

(Translated from the original Portuguese by Blanche Mendonca)

Brazilian director Fernando Meirelles has made a film of Saramago’s novel Ensaio Sobre a Cegueira / Blindness (1995). An epidemic of blindness starts to spread in a nameless city. People are forced to rely on each other when their natural faculties have left them. The ensuing experience of quarantine and the subsequent degradation leads the reader to a concept of blindness, allegorical, if not misleading.

This slow elliptical style of Saramago’s narrative sucks the reader into the vortex of the novel. It demands much from the reader. Long sentences often with no punctuation or paragraphs stretch into pages. The process of the making of meaning is as important as where the narrative leads us. This self-referentiality makes the novels many-layered, and virtually an exercise in epistemology or the theory of knowledge. In both form and content this is a master at work.

In a weekend interview last year Saramago (84) angered the Portuguese by predicting that Portugal would become Spain’s 18th semi-autonomous region. There was, he felt, ‘everything to gain from a territorial, administrative and structural integration.’ Portuguese poet and Socialist Party founder Manuel Alegre said Saramago had won the 1998 Nobel Prize by writing in the Portuguese language ‘which is part of our soul and will never be integrated into Spain.’ The issue has been resolved thanks to the European Union, wrote Pedro on a Spanish website.

The Portuguese government is now considering a standardization of the Portuguese language which would require hundreds of words to be spelled the simpler Brazilian way. The debate has been passionate between the erstwhile colonizer (Portugal) and the erstwhile colonized (Brazil), but Saramago (85) nimbly commented ‘We have to get over this idea that we own the language. The language is owned by those who speak it, for better or for worse.’ For a person who preached the ‘sermon of the fishes’ on the river Douro this was unremarkably astute.

At 84 Saramago was planning his next novel. ‘Maybe it is my last book’ he had said. ‘When I wrote Pequenas Memorias (2006) I wondered if the cycle was now complete. I had for the first time in my life a sense of finitude, and it was not a pleasant feeling. Everything seemed little, insifignicant. I’m 84. I could perhaps live another three, four years. The worst that death has is that you were here and now you are not.’ And later ‘I can’t complain. The things you think are a big deal are not so big. I’ve won the Nobel prize. And so?’

In autobiographical mode, in his last novel Pequenas Memorias / Little Memories Saramago returns to his childhood. ‘I have written memoirs of my youth,’ he says, ‘and I felt young as I was writing them; I wanted readers to know where the man I am today came from. So, I focused on the years from four to fifteen.’

Almost 10 years before that Saramago, in his Nobel Laureate speech recalled his childhood and the final moments with his grandmother and grandfather who were dying. It used to be so cold that they used to sleep with the piglets to keep them warm. It is a world which redeemed itself – simply because ‘in it lived people who could sleep with piglets as if they were their own children, people who were sorry to leave life just because the world was beautiful; and this Jeronimo, my grandfather, swineherd and story-teller, feeling death about to arrive and take him, went and said goodbye to the trees in the yard, one by one, embracing them and crying because he wouldn’t see them again.’

Throughout his life Saramago looked to see that vision of humanity in the world. There were many times when he had to open his mouth against what he felt was wrong. It could have been a still small voice in the wilderness but it is the voice of the prophet for our times ‘who with parables sustained by imagination, compassion and irony continually enables us once again to apprehend an elusory reality’ (Nobel Prize citation).

————————————————————————————-

(Saramago passed away on Friday, 18 June 2010 at his home on the Spanish Canary island of Lanzarote.)

All India Radio, New Delhi broadcast as an illustrated talk on the Rajdhani channel of AIR on 21 May 2008.

(Brian Mendonça, is a poet. He has a collection to his credit Last Bus to Vasco:Poems from Goa (2006). He is working on a sheaf of poems called ‘A Peace of India -Poems in Transit’.)

Will somebody be kind enough to write about John Elia Sb ,Dushyant Kumar Sb,Sharat Chandra Sb ,Nirala ji,Majaz sb,Neeraj sb,Amrita ji,Prem chand sb. etc our own lesser known but more sensible then many greats of west.Noble price is so much controversial that a whole book can be written on it.Nearest mortal to a prophet, Mahatma Gandhi was not given this price we all know why.

SHAFFKAT

Will somebody be kind enough to write about John Elia Sb ,Dushyant Kumar Sb,Sharat Chandra Sb ,Nirala ji,Majaz sb,Neeraj sb,Amrita ji,Prem chand sb.and many more, our own lesser known but more sensible then many greats of west.Noble price is so much controversial that a whole book can be written on it.Nearest mortal to a prophet, Mahatma Gandhi was not given this price we all know why.

SHAFFKAT

I love to learning more on this topic if possible, as you gain expertise, will you update your blog with more information?